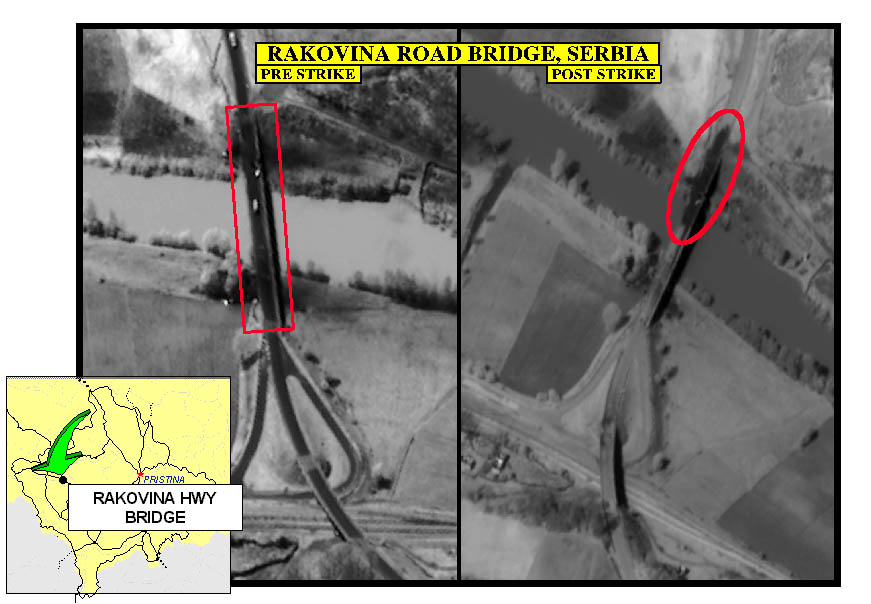

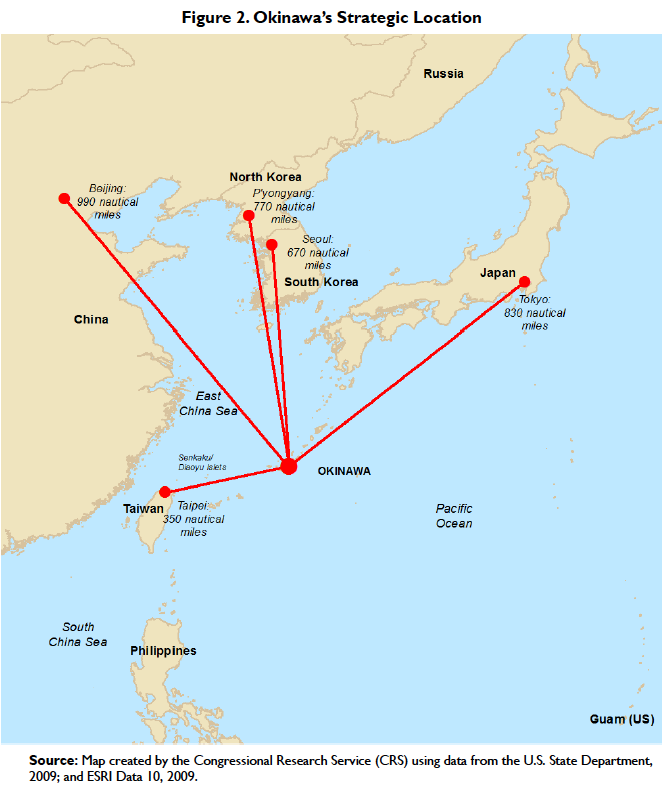

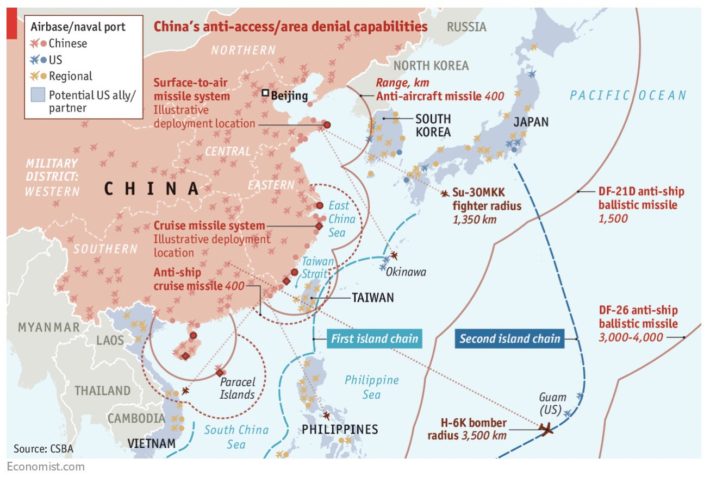

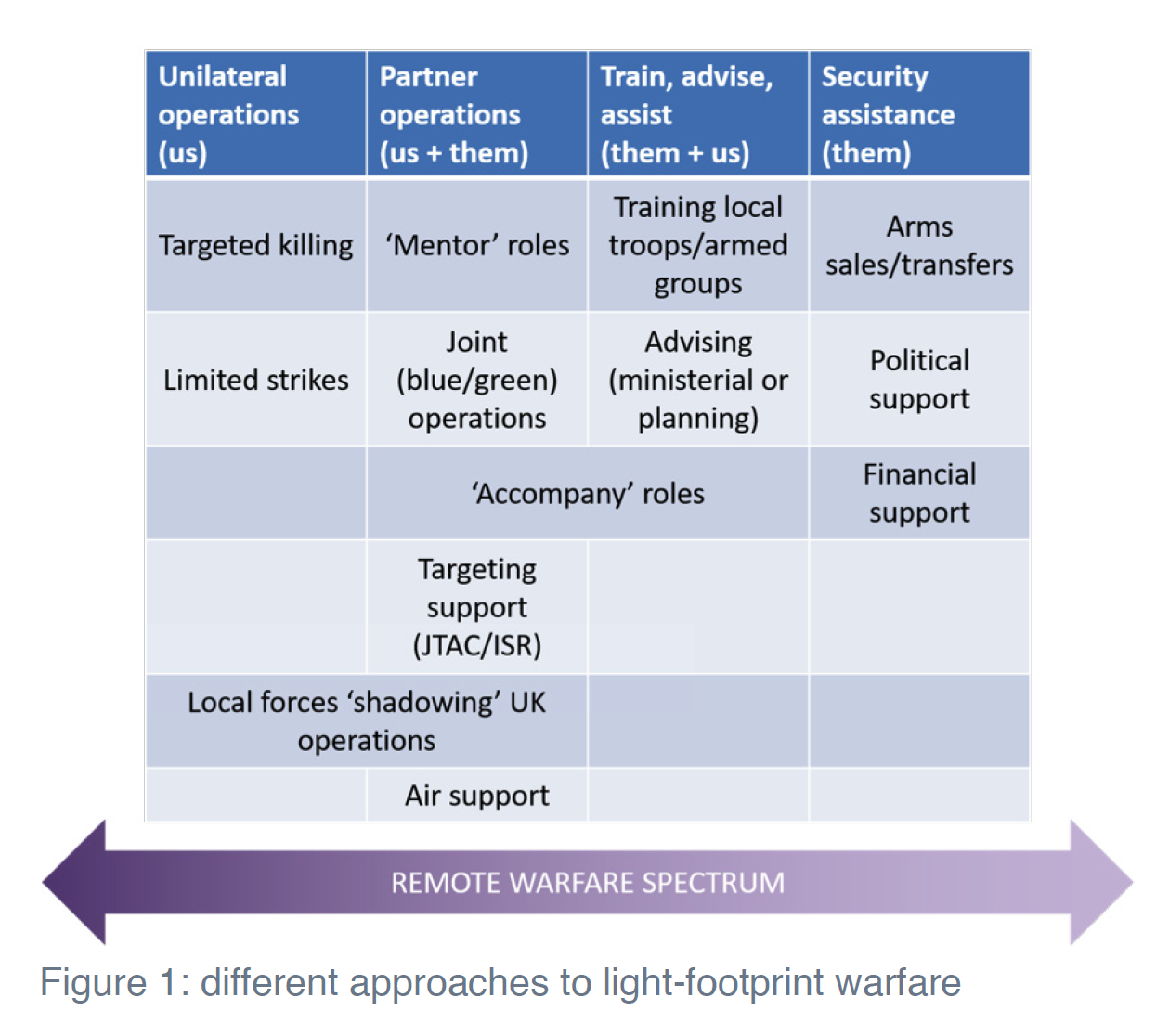

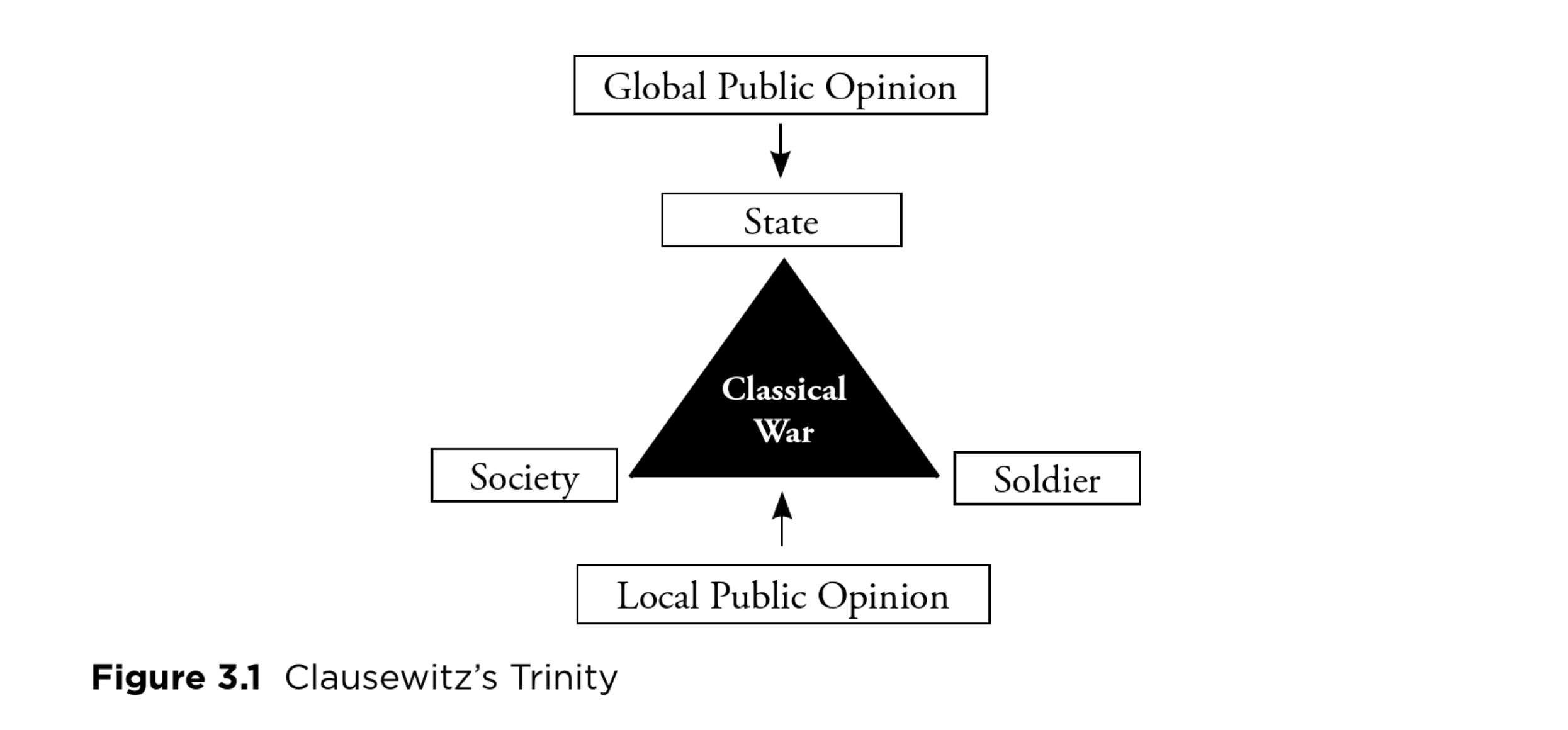

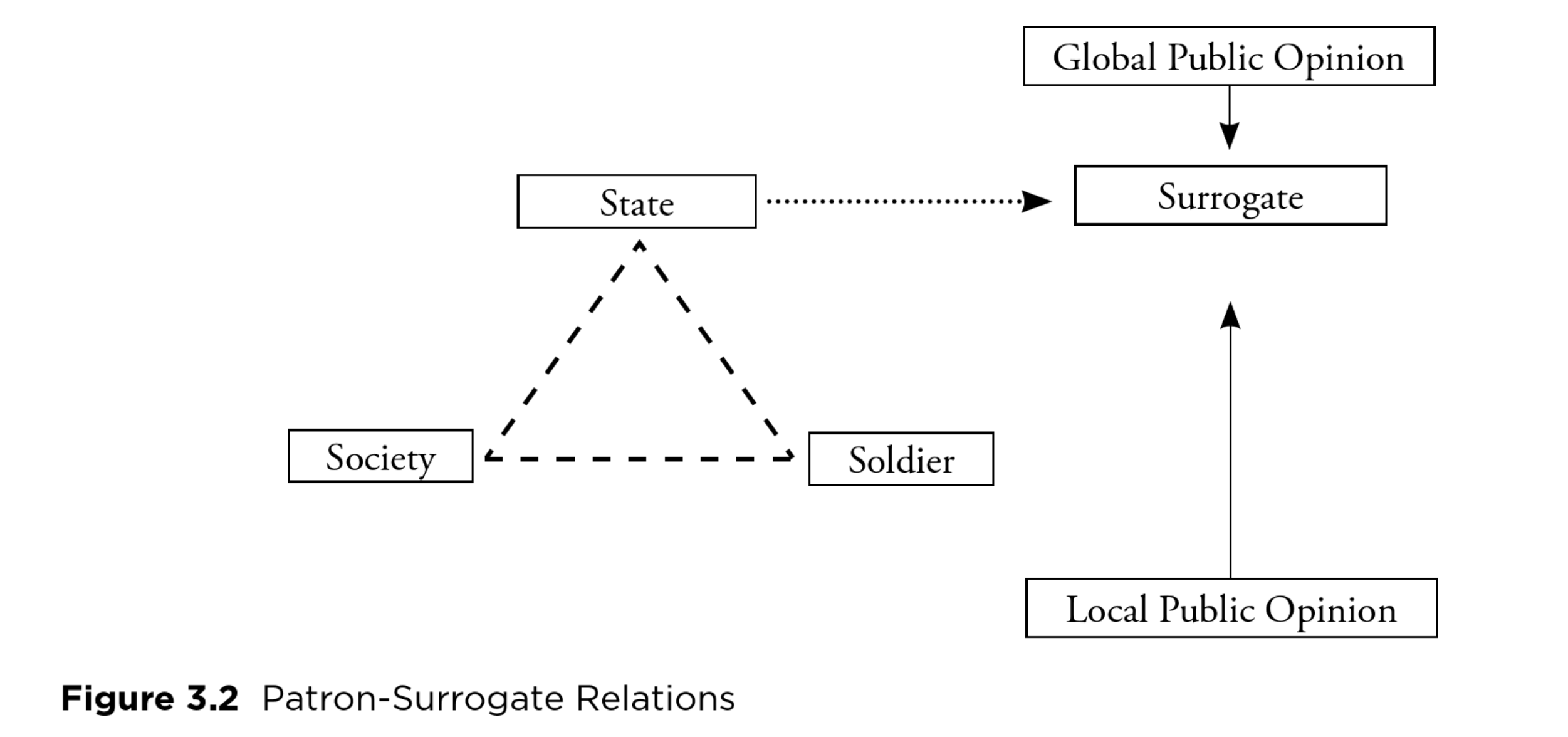

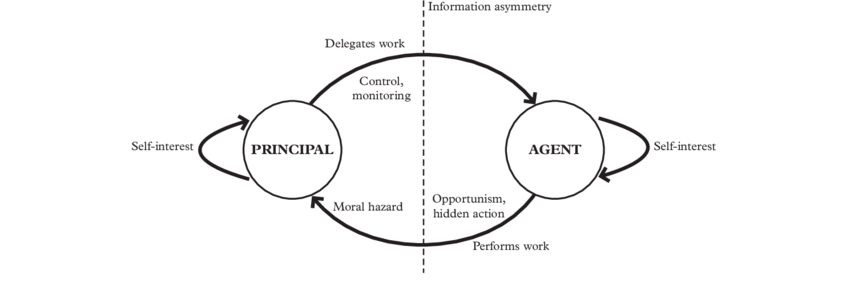

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Dirty Wars ## Remote Warfare ### Jack McDonald --- class: inverse # Lecture Outline .pull-left[ Is remote warfare new? Why is it now seen as a problem? ] .pull-right[ - War at a Distance - "X" Warfare - Principal-Agent Relationships in War - Distance and Closeness in Remote Warfare - Conclusions and Connections ] ## Main Points Distance and power projection have always been important features of war and warfare Contemporary proxy warfare can be differentiated from prior eras due to possibility of close-coupling of forces The concerns regarding remote warfare is more about political distance and closeness than physical distance ??? /// --- class: inverse # Part 1: War at a Distance ??? --- # Contemporary Military Intervention .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[  ] ??? --- # Power Projection Problems > We define power projection as the deployment of military force beyond one’s own capital. In this sense nearly all states possess some ability to project power; however for most states that capability is extremely limited. We are principally interested in states that can project large amounts of military power globally. The more power a state has and the less that power decays over distance, the higher its power projection capability. Thus, there are two variables that interact to determine a state’s ability to project power: the amount of power a state has, and the degree to which that power decays over distance... > It is only very recently that technological innovation has lowered the cost of power projection enough to allow states to fight, interact, and extend political order on a global level. Without the ability to transport forces over great distances, great powers would be confined to their own regions, and there would be no global system as we think of it today. As the cost of power projection has decreased, the world has become smaller, and a set of distant and separate international systems have been merged into a single global system. Jonathan N. Markowitz & Christopher J. Fariss, _Going the Distance: The Price of Projecting Power_ ??? --- # Bases and Power Projection .pull-left[   ] .pull-right[  ] ??? Philippines ran BRP Sierra Madre aground in 1999, staffed by Marines ever since --- # Sovereignty and Distance > The vision of a shrinking globe superintended by a ‘global policeman’ and its allies has weighty policy implications. It leads to a logic of ‘threat eradication’, where states pursue absolute security by destroying opponents, as opposed to containment, where states might seek to limit and interdict the capabilities of adversaries more incrementally. Visions of the West’s far-flung interests underpin the call for ever-more garrisoning and counter-insurgency ground wars in the future. It drives the movement towards a permanent state of exception and emergency, where the state accumulates new powers with few checks or scrutiny. Patrick Porter, _Why Distance Matters: Putting the ‘Geo’ Back into Politics_ ??? Dirty wars can help us understand this --- class: inverse # Reflection Question .large[Do you think Western states should adopt a policy of containment rather than engaging in interventionist conflicts?] ??? --- class: inverse # Part 2: "X" Warfare ??? --- # The "naming game": What is new? > Aiming to define the ‘new newness’ of interventionist warfare, scholars have entered into something of a coining contest. Drawing on the notions of ‘(counter-)netwars’ (Arquilla and Ronfeldt, 2001), ‘network war’ (Duffield, 2002), and Hardt and Negri’s (2004) ‘global civil war’ (2004), we see labels such as ‘securocratic war’ (Feldman, 2004), ‘chaoplexic warfare’ (Bousquet, 2008), ‘coalition proxy warfare’ (Mumford, 2013), ‘transnational shadow wars’ (Niva, 2013) or simply ‘remote warfare’ (Watts and Biegon, 2017). > Paying tribute to Zygmunt Bauman’s (2000, 2001) liquidity vocabulary and Derek Gregory’s (2011) notion of ‘everywhere war’, we propose to use the term ‘liquid warfare’ to highlight how conventional ties between war, space and time have become undone. Liquid warfare is about flexible, open-ended, ‘pop-up’ military interventions, supported by remote technology and reliant on local partnerships and private contractors, through which (coalitions of) parties aim to promote and protect interests. Liquid warfare is thus temporally open-ended and event-ful, as well as spatially dispersed and mobile. Jolle Demmers and Lauren Gould, _An assemblage approach to liquid warfare: AFRICOM and the ‘hunt’ for Joseph Kony_ ??? --- # Proxy Wars .left-66[  ] .right-66[ > an international conflict between two foreign powers, fought out on the soil of a third country; disguised as conflict over an internal issue of that country; and using some or all of that country’s manpower, resources, and territory as means for achieving preponderantly foreign goals and foreign strategies. Karl Deutsch, _External involvement in internal war_ ] ??? --- # Remote Warfare .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[  ] > Remote warfare, at its most basic, is a term that describes approaches to combat that do not require the deployment of large numbers of your own ground troops. In contrast to the extensive NATO operations in Iraq and Afghanistan that characterised 2001-2014, a second wave of post-9/11 wars has seen the mobilisation of ad-hoc coalitions of the willing to counter groups like IS, al-Qaida, Boko Haram, al-Shabaab, or the Taliban. > Many aspects of remote warfare are not new. Wars have been fought alongside and integrated with allies and partners since antiquity. Emily Knowles and Abigail Wilson, _Remote Warfare: Lessons Learned from Contemporary Theatres_ ??? --- # Surrogate Warfare   ??? --- # Surrogate Warfare 2 > Starting with the RMA in the 1990s, surrogacy in war has changed dramatically. Amid the technological progress in the field of precision-guided munitions (PGMs), unmanned platforms, cyber technology, and artificial intelligence (AI), surrogate warfare will increasingly rely on the machine as the surrogate of choice. > This chapter identifies three technologies that make surrogate warfare by machine a more likely reality of warfare in the twenty-first century. First, the evolution of drone technology offers some interesting insights into the birth of technological surrogates. Second, the emergence of cyber technology has opened the cyber domain as a domain for surrogacy par excellence. Here particular attention is devoted to social media and its role in subversive operations. Finally, this chapter will open up the discussion on technology as a surrogate, focusing on emerging autonomous weapon systems (AWS)—a paradigmatic shift from the way humans have fought wars throughout history. AWS can be combined in both the physical and digital domains. These weapons for the first time in human history will be able to fully substitute human capability on the battlefield. Andreas Krieg and Jean-Marc Rickli, _Surrogate Warfare: The Transformation of War in the Twenty-First Century_ ??? --- class: inverse # Reflection Question .large[Do you think that surrogates and proxies can shield states from domestic and international opinion?] ??? --- class: inverse # Part 3: Principal-Agent Relationships in War ??? --- # Principals and Agents .pic70[] > Principals typically employ agents because they lack the appetite or attributes necessary to directly achieve the aim themselves... > Typically, though, the aims of the agent will diverge somewhat from those of the principal, while the act of delegation invariably means that the principal will lack complete oversight of the agent's behaviour. Hence, neither party can be entirely certain of the other's commitment or intentions. This information asymmetry creates powerful incentives for the agent to ‘foot-drag’, delaying or shirking activity to secure (more) reward from the principal, even when their goals closely align. Moreover, the more the interest asymmetry, the more the agent will benefit from diverting or misappropriating the principal's resources in furtherance of their own divergent aims, known as agency loss. Alex Neads, _Rival principals and shrewd agents: Military assistance and the diffusion of warfare_ ??? --- # Proxies and Surrogates > In presenting an alternative to direct war, proxy wars answer _the_ essential Clausewitzian problem: “[H]ow to make force a rational instrument of policy rather than mindless murder? How to integrate politics and war?” (Betts, 1997, p. 8). Strategic interaction is a productive framework allowing policy and scholarly debate to move forward by shifting the focus on strategic bargaining between actors. Through this, we can then appreciate the extent to which proxies are invested in warfighting, how other states might respond to proxy strategic environment, and how to balance escalation with inaction or retreat. Vladimir Rauta, _Three Generations of Proxy War Research_ ??? --- # Contractors and Contracted Companies > The uniqueness of the special arrangement between state-run enterprises and Russian PMSCs like Moran and Wagner suggests the informal networks that constitute power in Russia exert considerable sway over PMSCs. Moreover, the intersecting links between individuals affiliated with various contingents of Russian PMSCs and separatist militias, Russian military associations, veterans’ organizations, and self-proclaimed mercenary communities offline and online reinforce the notion that the Kremlin covertly enables, endorses, and encourages their activities. It may very well be that many or even all Russian PMSCs operating in Syria and Ukraine meet the legal standard for a force for which Russia has overall control. Still, a not insubstantial amount of evidence would need to be compiled from primary sources and witnesses to make the case that the Kremlin maintains effective control over these PMSCs in the classic top down sense. That, however, is the point of the strategy. Candace Rondeaux, _Solving the Puzzle of Russian Proxy War Strategy_ ??? --- # Force as a Service > the militarisation of cyberspace may actually be the result of a demilitarisation of cyber conflict, as the main actors in cyber conflict are not actually military actors. Both the dominant role of foreign-intelligence and security agencies (as opposed to military actors) in cyber operations, and the use of proxies (either private contractors or other non-state actors) in cyber conflict, illustrate that, in practice, cyber conflict largely takes place outside the parameters of international humanitarian law. Other principles of international law still apply to interventions by intelligence services and proxies below the threshold of armed conflict. International law writ large is silent on espionage, but not on covert paramilitary actions or clandestine intelligence activities with disruptive effects. Many states use proxies precisely to render their potentially illegal actions deniable. Sergei Boeke and Dennis Broeders, _The Demilitarisation of Cyber Conflict_ ??? --- class: inverse # Reflection Question .large[Where is the principal-agent problem relevant to other aspects of international politics that you find interesting?] ??? --- class: inverse # Part 4: Distance and Closeness in Remote Warfare ??? --- # Civil/Military Relations .left-66[ > It has been said that my decision to ignore my orders from London and intervene militarily in the civil war – which is what happened over the next days and weeks – was cavalier. It wasn’t. It was the result of hard-nosed analysis. > My objectives were far more ambitious than simply organising an evacuation of British nationals and other ‘entitled persons’. In fact, we were so quick in getting on with our planning to intervene in the war that my orders from London, which arrived three days later, were barely relevant to what we were doing. They were exclusively concerned with the conduct of an emergency evacuation. They had nothing in them about helping the UN and nothing about creating a military alliance to help Kabbah. General Sir David Richards, _Taking Command_ ] .right-66[  ] ??? Purchase of military commissions banned in the UK in 1871 Operation PALLISER in Sierra Leone 2000 Unholy alliance and UN forces to resist RUF --- # Command, Control, and Killing > Wald had been leaning back in his chair, occasionally putting a Styrofoam coffee cup to his lips to catch the shells of sunflower seeds he was chewing. When the silent infrared picture suddenly flared in the familiar white blossom of an explosion, the three-star general sat bolt upright. > "Who the fuck did _that_?" Wald and Deptula blurted in unison, staring at each other in wide-eyed shock as men poured out of the building they had wanted to bomb and dashed around the courtyard of the compound in Afghanistan. Richard Whittle, _Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution_ ??? Whittle Quote (pp. 259-260) Coalitions and warfighting Internal coordination and Control Pentagon drone screens Sierra Leone example --- # Sovereign Decisions .pic80[  ] > On many Tuesdays during his presidency, Barack Obama convened an extraordinary meeting in the Oval Office. His national security aides would show him mug shots and short biographies of alleged terrorists. The suspects were Yemenis, Saudis, Afghans, and sometimes Americans; they included men, women, and teenagers. The president would look over these chilling “baseball cards,” as one aide called them, and pick which subjects should be put on a kill list to be assassinated on his orders. Kathryn Olmsted, _Terror Tuesdays: How Obama Refined bush's Counterterrorism Policies_ ??? --- # Interdependent Errors .pic80[  ] > MSF is disgusted by the recent statements coming from some Afghanistan government authorities justifying the attack on its hospital in Kunduz. These statements imply that Afghan and U.S. forces working together decided to raze to the ground a fully functioning hospital – with more than 180 staff and patients inside – because they claim that members of the Taliban were present. This amounts to an admission of a war crime. Christopher Stokes, general director of Médecins Sans Frontières ??? Kunduz hospital 2015 --- class: inverse # Reflection Question .large[Is it always wrong for a military commander to commit their troops and country to war without explicit political direction?] ??? --- class: inverse # Part 5: Conclusions and Connections ??? --- # Key Issues .large[ We live in a world of flexible power projection, but our way of understanding right and wrong in war is state-centric Remote warfare is ultimately about political connections and interdependence, not distant killing Proxy wars are not going away! How contemporary democracies reconcile themselves with the use and support of proxies is a big issue ] ??? --- # Key Questions .large[ Is it inherently wrong to support conflict in another country for your own benefit? How can we bring peace to internationalised conflicts? What is your opinion about political leaders making tactical military decisions? ] ???