Say what you want about the retreat from Basra, Dude, at least it’s a definable event

The penny dropped that this year I get to teach students who were born after the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The last such milestone was “born after 9/11” and in my head, the next one is “born after Bin Laden was killed”. This got me thinking: what might students actually consider to be a contemporary conflict? Like, what are the salient wars that are actually new to them, not a decades-long hangover from the time that they were toddlers? More to the point, what might British military operations look like to someone for whom the Coalition war against ISIS kicked off roughly half a lifetime ago?

As a rough division of time: 2014 and before is now pretty much ancient history. It’s the wars that happened when you were still in primary school. My mum took me to some demonstrations against the first Gulf War when I was a kid but it is fair to say that by the time I turned 18 Desert Storm and the like was little more than a hazy memory. I’d say the next kind of division is (in the British school system) the time between the start of secondary school and finishing GCSEs. This is old history. Personally speaking, this is a lot of the “big events” of the 1990s - Yugoslavia, Rwanda, the first Chechen war. It’s like stuff that you can remember happening but is kinda done by the time you’re an adult. Lastly, there’s the actual contemporary conflicts, something like the couple of years before you hit university. For me this was Kosovo 1999, Sierra Leone, and 9/11 (which occurred a couple of weeks before the start of term).

I think as adults and educators we might laugh at the proposition of taking something like a two year slice of conflicts to count as contemporary warfare. We think in terms of decades, sensible peridisations (like “post Cold War”), and the 4/5 year plans of budgets and national security strategies. All of that makes sense in analytical terms, but at the same time it is perhaps not as different to imposing a scheme of “upto 2 years ago = contemporary, 2-7 = old, 7+ = ancient” onto recent history as we might like to think.

A part of this, I think, is that we are somewhat numb to the plague of interminable conflicts that have been kicking around since 9/11. The fact that it is 2021 and we’re all wondering if America might finally get the answer right to “Will they/won’t they admit defeat in Afghanistan this year?” is perhaps the best emblem of this. That war has been going on for over half my lifetime, which I suppose is roughly how an 18 year old might view the Coalition air war against ISIS.

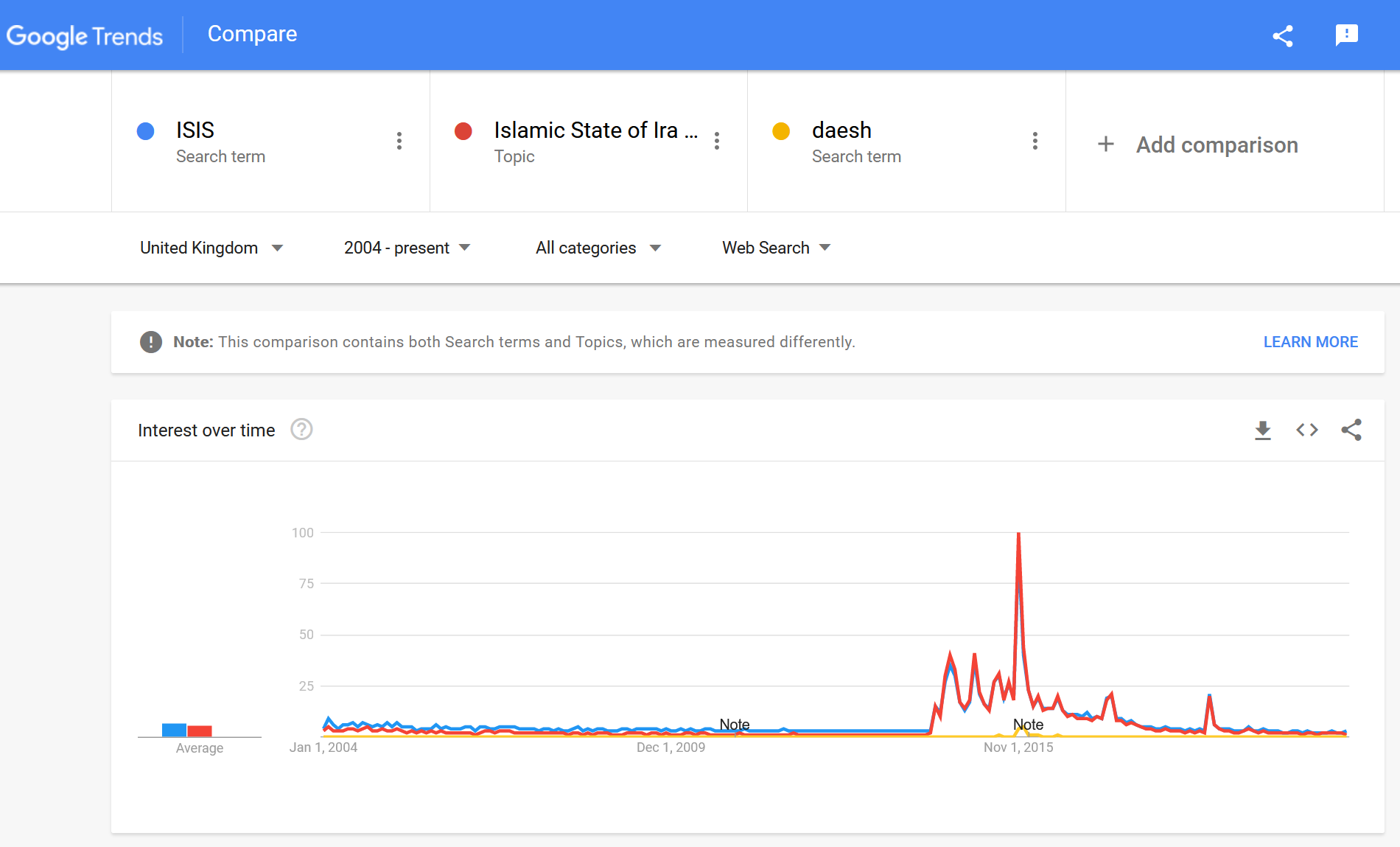

So what does Britain’s recent military history look like to an 18 year old? Well, Sierra Leone and the 2003 invasion of Iraq are now in one way functionally equivalent to the First World War - it happened before they were born. All the big events: the Basra pull-out, the expansion of the war in Afghanistan, and the subsequent withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq, David Cameron’s Libyan adventure - these are all ancient history. To someone born in 2002/3 the peak of the air war against ISIS is by now old history:

Perhaps to reenforce this point, if I were to design a course from scratch on contemporary warfare, I don’t think the 2003 invasion of Iraq would make the cut, at least not as a standalone topic in and of itself. By definition, “contemporary” is a shifting label, moving with us as we get dragged into the future. The 2003 invasion is undoubtedly one of the single most important events of the early 21st century, but given resource constraints (10 lectures, 14 lectures, 20 lectures, take your pick) I think students would be better served by a lecture on Iraq after ISIS than reprising the run up to 2003.

To introduce students to contemporary conflict, I think a pretty defensible list of case studies would (in no particular order) look something like this:

- The Tigray War

- 2nd Nagorno-Karabakh War

- Israel-Palestine (Recent Gaza conflict)

- China-India border clashes

- Colombia/Catatumbo

- Battle of Marawi

- Myanmar/Rohingya

- Conflict in the Niger Delta

- Iran/Saudi Proxy War

- Yemen Civil War

- Coalition Warfare and the Battle of Mosul

- Russian and Turkish intervention in the Syrian Civil War

- Second Libyan Civil War

- US-Iran Persian Gulf Confrontation (2019-)

- Afghanistan after 2012 NATO Drawdown

- MONUSCO and Conflict in the DRC

- Conflict in the Sahel

- Drug “War” in Mexico

- Ukraine

- Maritime Confrontations in the South China Sea

I’m sure there’s thing that could be chopped/changed/re-combined. There are also some big conflicts that don’t make this list (The wider historical conflict in Colombia, recent civil war in South Sudan). It misses some big aspects of international politics (nuclear weapons, cybersecurity). By definition, no such course could really be complete, but I think the above would provide a good intro to how/why people are killing each other in the present day, and some of the big conflicts that people are worried about in the near term. A conceptual/thematic course would look completely different from the above.

From the British perspective, what is most interesting about all of this is perhaps how few defining events there are threaded through this (Mosul aside). There is the steady diet of British military operations: coalition warfare, overseas peacekeeping operations, training missions, and likely a fair few people running around in secret doing stuff we won’t hear about unless it goes horribly wrong. But there’s no signature events like the 2003 invasion, the retreat from Basra, Helmand, the toppling of Gaddafi’s government in Libya. Looking at war in the contemporary world, we find British military power being thrown at indeterminate conflicts that wax and wane without an apparent end point.