Integrated Review Guide

This is a guide for students, currently complete up to the Strategic Framework Section.

Introduction

This is intended as a “zero-knowledge” guide to reading the UK’s 2021 Integrated Review policy document: “Global Britain in a competitive age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy” link. It is aimed at first year undergraduates who may have little or no knowledge about how the UK’s political system works, and therefore aims to provide the reader with a lot of background knowledge that more knowledgeable readers might not require/need.

The Integrated Review does not systematically number paragraphs. Where paragraph numbers exist in a section, the paragraph numbers below directly correspond to these. Where paragraph numbers are not used in a section, you’ll have to count paragraphs from the start by hand I’m afraid.

Front Matter

There’s four elements on the front page: seal, title, pretty picture of the UK, and series number (“CP 403”).

The Integrated Review is a government publication (hence the HM Government seal), and the “CP 403” identifies it as a Command Paper. These are government publications that are presented to Parliament.

For more details, see https://www.parliament.uk/about/how/publications/government/

As such, this is an example of a fundamental political process in the UK: the government says something, then presents it to Parliament for discussion and review. This was presented to Parliament on the 16th of March 2021 by the Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyheDGxa0vc

With regards to the photo, I think the one aesthetic choice that is important to note is that it effectively says nothing. It is a photo of the UK, but you’d have to squint and tilt your head sideways (and know what the UK looks like) to get that. It is, however, more glossy than the front cover of the previous review, the National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015:

Now, with all of that out of the way, the title:

Global Britain in a competitive age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy

The Integrated Review isn’t even the Integrated Review, that’s just the sub-title! Actually the IR is the name for the review, and the main title was added at the end. Announcement statement here

Three things are important in the title. First up: “Global Britain”. This is a statement that Britain is to be perceived as, and thought to be, a global power. Second: “a competitive age”. This reflects ongoing debates in international politics about “great power competition”. Specifically, this is nodding towards the fact that the IR is trying to figure out Britain’s place in a world where the US and China see themselves in a competition for hegemony, and other big countries such as Russia are seen as challenging the post-Cold War order.

Now we get to the sub-title: “The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”.

First thing to note is that this distinguishes between security, defence, development, and foreign policy. Why distinguish between security and defence? Why distinguish between development and foreign policy?

The reason for the title is actually a clue to the relationship between this document and the government departments who actually have to implement this. Although an outward focused document, the contents are relevant to all government departments/organisations concerned with providing security to the UK (e.g. the Cabinet Office, the Home Office, the National Security Secretariat). Specifying defence in the title indicates that it is important for the Ministry of Defence.

But why separate out development from foreign policy? Well, when this review was first announced, the UK had a government department dedicated to overseas development - the Department for International Development - as well as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, whose remit is foreign policy. These two were rolled into one department, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office in September 2020 (the perceived loser in this event is the one whose department name got tagged to the end of the other).

But you can’t change the name of the IR mid-process, so the name sticks. One thing to reflect, therefore, is that by the time this document was published, the name and process reflected political structures that were already out of date in domestic UK politics.

Contents

Things to note before we look at the structure proper:

2030: This date pops up in both the PM’s foreword, and the third section (“The national security and international environment to 2030”). This document, published in 2021, is looking ahead about ten years, as a plan for the future.

Annex A and the Spending Review 2020: This document is about what the government is going to do, which is also a way of saying what the government is going to allocate resources to. One key resource is money, and that’s why to understand how meaningful any of this is, we have to look at what’s been allocated to it.

The Spending Review 2020 is the Treasury’s plan for what the government is going to pay money for, why it is going to pay it, and how it is going to go about raising the money that it has committed to spend.

The SR2020 is a big document: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spending-review-2020-documents/spending-review-2020

One thing to note about all of this is that “Strengthening the UK’s place in the world” is the sixth main section of the document. Everything the IR is concerned with is a fraction of the Treasury’s overall concerns (or government efforts as a whole). Secondly, if you look at the Departmental settlements, the Treasury is funding departments through to 2024-5. This means that while the IR is explicitly looking forwards 10 years, the Treasury has only explicitly funded the plans for about half this period of time. In the IR itself, it explains that the Strategic Framework goes to 2025.

Okay, so onto the structure of the IR.

A good initial way to understand these kinds of documents is to try and work out their priorities in terms of attention given to different topics.

The obvious core to the document is section IV - the “Strategic Framework”. Out of 99 core pages (excluding front matter and appedicies), 63 are dedicated to this section.

The IR consists of a short foreword from the PM (3 pages), some vision statements and infographics from the PM (4 pages), an overview (13 pages), an assessment of the international environment (10 pages), the strategic framework (63 pages), and a section on implementing the review (4 pages).

One thing to keep in mind is that these kinds of documents are designed to be read in whole by people who really care about the topic, and also designed so that people can get the gist of what’s going on without reading the whole thing. The PM’s foreword is a nexus between the political nature of the document (it is tied to Boris Johnson’s government and its political priorities). The overview is what will give you a very short and crisp understanding of the what’s going on. The foreword is therefore going to be where you’ll find some stuff that is tied to contemporary political discourse in the UK and perhaps partisan framing of some issues.

Even though it might feel like you can just skip to the overview, the foreword is important for understanding the document itself.

The third section, “The national security and international environment to 2030”, is going to tell you what the foundational assumptions behind the document are in detail. For this reason, it is important to read, but also keep a critical eye out - the nature of such a section is that it has to identify and explain key assumptions and priorities, and therefore it has to leave a lot of other stuff out.

So, the structure of the strategic framework.

The point of a document like this is to give the whole of government an understanding of how and why the UK is going to organise itself to engage with the world in a particular way. Importantly, this is about conceptual organisation. The world is a complicated place - in order to have a hope of understanding it, you have to use concepts to connect related issues together and simplify things. However, the danger is that two different people, or departments, will end up with different conceptual maps, reflecting their own view of what is important, and how things tie together.

For that reason, the strategic framework (and the rest of the document) provides a way for officials and policymakers to collectively understand what’s going on, why it’s happening, and how the government is going to respond. Understand it as a specific collective simplification of international politics.

The value of this document (and others like it) is that its choice of concepts can tell you about how the government collectively evaluates its situation, and also how it seeks to engage with the world.

Let’s just look at the big sub-headings:

- Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology

- Shaping the open international order of the future

- Strengthening security and defence at home and overseas

- Building resilience at home and overseas

These don’t perfectly map to “Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”, and that’s the point: the document is saying that out of all the things that could possibly be covered within these domains, these are the four priorities.

Lastly, before we move to the document proper, I think we need to note the italicised sub-elements in the strategic framework:

- The UK in the world: A European country with global interests

- The Indo-Pacific tilt: a framework

- The nuclear deterrent

The fact that these things pop out in the contents page is important. It gives the reader a chance to flick to a specific page to check exactly what’s going on with each term. Their importance is, I think, underlined by the fact that one of them is about the UK’s nuclear deterrent capability. Nuclear weapons are a big deal! The first term appears to be related back to the “Global Britain” discussion earlier: it is a self-description of what the UK is, and should be, and therefore a key reference point.

But what about “Indo-Pacific tilt”? If you have no prior knowledge of UK defence and foreign policy debates, this term is likely unknown to you as it is the unique term on the contents page. It is, however, very important. The reason for this is that the inclusion of IPT here reflects that the document is taking a side in some pretty weighty debates that are, for the time being, outside the scope of the document itself.

Defence and foreign policy debates are characterised by different interpretations of what is the best way forwards for a particular country. Where should the diplomats and trade negotiators spend their time? What kind of army do we need? What kind of ships should we build? These are subsidiary questions to an overarching notion of what kind of engagement is good for a country, and what regions of the globe it should engage with.

When you’re a superpower (the US, China), you can afford to engage with everywhere in at least a minimal way (whether or not you choose to do so is a different matter). When you’re a small state like Singapore, you can’t afford to have a diplomatic presence across the world (any form of diplomatic presence requires money to keep the lights on, etc), so you have to be selective. The UK is somewhere in between: once an Empire, now a very rich country (member of the G7), but while we can afford to have a huge network of diplomatic missions, we can’t afford the kind of global footprint that the US has, and China is quickly developing.

Some people think the UK should be focusing upon Europe and building the ties and capabilities to deter Russian aggression. Others think we are best placed to split our focus between Europe and the Middle East. Others think we’re better off engaging with countries across Africa. But a substantial number of people think we should be focusing our resources and attention on building ties in the Indo-Pacific region. Pretty much everyone thinks we should continue to be close allies of the USA though.

The choice of “Indo-Pacific” is itself a political conception - tying together the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean into one area of engagement and concern. The IPT is basically indicating that the UK will shift attention towards this region, both in political and military terms.

I’m highlighting this now because what is important for you to know is that this is fundamentally about trade-offs. A critical engagement with the IR requires you to understand the tradeoffs that are implicit in the document itself, but you are unlikely to get a full understanding of these tradeoffs from the document. After all, it’s trying to sell the selected tradeoff as the right thing to do!

Every state has to make trade-offs - the USA is no exception in this regard. The problem for non-super powers like the UK is that the USA can screw up and recover, whereas if the UK makes the wrong trade-off it can be catastrophic. This is not to say that the US can’t make catastrophic decisions, but the US could cut its army in half and regenerate it relatively quickly, whereas if the UK’s army was cut in half tomorrow, it would lose key areas of expertise that would be impossible to replace at speed.

So what I’m saying is that before jumping to any conclusions about whether or not something is the right thing to do, we first need to understand what the actual choices being made are.

Now, onto page 2.

I. Foreword from the Prime Minister

- Covid-19

- “Build back better” is a reference to the UK government’s economic recovery plan after the Covid-19 pandemic: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/build-back-better-our-plan-for-growth

- Don’t mention the word “Brexit”.

- Two points:

- If you are unfamiliar with UK politics, Scottish nationalism and separatism is a big issue. The Scottish National Party (SNP) is the third biggest party in the UK Parliament, and, despite losing the last independence referendum, seem intent on securing a new one in the near future. Hence, the focus on the Union as a common identity/source of strength.

- The emphasis on soft power is that the UK has a huge global cultural influence, although whether that translates into achieving the UK government’s policy priorities anymore is currently questioned. It is widely regarded that the UK’s separation from the EU and approach to Brexit has torched the UK’s reputation in a number of areas.

- Two points:

- Easy to pick at the notion that “Few nations are better placed” but no country is going to publish a document that says it is mid-rank on anything, so accept that this forced pre-eminence sans evidence is part and parcel of these kinds of documents.

- Note the tone by which democracy is discussed - this reflects wider debates about whether authoritarianism will make a comeback in international politics, and whether democracies can successfully compete with major authoritarian states like China and Russia.

- The term “international order” is important here. There have been many recent debates about the “liberal international order”, with reference to the rise of China, and the fact that it seeks to re-shape international order. One point to make is that the current international order does effectively favour democratic states. It is, after all, underpinned by the United States of America, the world’s leading democracy/hegemon. What’s interesting here is the use of the term “open and resilient international order” instead of “liberal international order”, when referring to effectively the same thing.

- Three points:

- Big hitters: people, homeland, democracy. Note that the term “homeland security” was heavily associated with America after 9/11 (it set up a “Department of Homeland Security”) but now the UK is starting to adopt this institutionally. In April 2021, the Home Office reorganised and created the Homeland Security Group, responsible for keeping the UK safe from the threat of terrorism.

- Defence spending is a key issue. NATO has a notional political target of 2% spending on defence from NATO member states. Many states fall short of this figure. The USA wants EU states to spend more on defence so that it doesn’t have to, therefore the 2.2% claim is a signal to both the USA and NATO that the UK is a good partner.

- The Salisbury attack was an attempted assassination of a former Russian military officer using a nerve agent, Novichok. The method of attack meant that both the agent and his daughter, as well as a UK police officer, were all affected and hospitalised. Subsequently, the discarded nerve agent dispenser (a perfume bottle) killed a person near Salisbury. Without naming Russia, the list of activities in this section are heavily associated with Russian activities, and Russia is blamed for the Salisbury attack.

- One thing to note about terrorism - the public perceives terrorist threats primarily through attacks, and the problem for governments is communicating the scope of terrorist threats that don’t result in attacks because the government has acted.

- This is a mix of organisations being stood up or re-organised (CTOC, NCF), copying Americans (the US White House has a “Situation Room” for Presidents to use when coordinating in emergencies) and a cornerstone Conservative policy (stronger borders).

- The UK government is betting on high tech industries for future economic growth. This is connected to wider debates about the future of the UK’s economy after Brexit, which caused significant disruptions in a number of sectors. This is therefore the government betting that the best way forwards for the UK is to concentrate on scientific research and the provision of digital services.

- Again, a policy marker - climate change being a big international issue.

- FCDO - as previously mentioned, created halfway through the IR process. Note that the UK spent below its 0.7% GNI target during the Covid-19 pandemic (0.5%), hence the signalled return to 0.7%. 0.7% is the UN’s Official Development Assistance target: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn03714/

- Britain wants to be seen as a leading global power. There are arguments that it remains a leading global power, but some argue that it has lost its place in global society after leaving the EU.

- For defence stuff, this is a key paragraph, and the terms will pop up again and again.

- HMS Queen Elizabeth - the UK will have two aircraft carriers capable of global operations. HMS QE is the first in service.

- Global deployment - the UK’s Royal Navy is now pretty much too small to spare enough ships to create a task group to sail to the other side of the planet, so the UK forms task groups with our allies. Task group is the collection of ships required to be a viable military formation (aircraft carriers need protection from other types of ship).

- The UK needs to be able to demonstrate interoperability because sailing ships is hard, and commanding a task group is hard, and doing so without learning how to work together effectively is even harder. To show that these kinds of military formations can be useful in a crisis situation (or worse), it is necessary to demonstrate that they can function well together.

- The other reason the UK needs to demonstrate interoperability is that the HMS QE currently has US planes on board, so what the UK is demonstrating is that even if it doesn’t have enough cash to fund 100% national capabilities, it can fund enough to be a leading partner among its allies.

- Yay optimism

The Prime Minister’s vision for the UK in 2030

- A stronger, more secure, prosperous and resilient Union

- Aspirational statements mostly covered in the PM’s foreword

- A problem-solving and burden-sharing nation with a global perspective

- “Problem-solving” - the UK wants to be engaged with the world

- “burden-sharing” - the UK is going to pay its way

- Note that the first thing that is highlighted is the fact that the UK is a permanent member of the UN Security Council. This is a key status marker in international politics.

- This section lays markers on relationships (the UK’s relationship with the US and the EU). Note the straightforward description of the US relationship and the very specific description of the UK/EU relationship, this is an indicator of how sensitive some of these terms have been in the UK’s Brexit debates.

- Last section is very important - key goals of being the key European partner in the Indo-Pacific (other EU states might want to be the same, and the EU might also want that status). Note the regions that are absent from the focus: Asia (including Afghanistan), South America, Central America. The last is important because a number of British territories and overseas dependencies are in this region.

- Creating new foundations for our prosperity

- “Firmly on a path to net zero” = “not giving a precise date for net zero”. The UK has, however, sharply reduced carbon emissions relative to other developed countries.

- The interesting paragraph here relates to global regulation. By exiting the EU, the UK is also exiting EU technology regulation regimes, such as the General Data Protection Regulation. The problem for the UK is that if its regulatory standards diverge from the EU, this will affect the UK’s ability to trade with the EU. Secondly, there is global competition with regulatory regimes, and it is not clear how the UK can carve out leadership here given that US/EU/Chinese domestic markets are far bigger.

- Adapting to a more competitive world: our integrated approach

- Again, aspirations, but fair ones. The UK has a substantial diplomatic presence and spends a lot on development assistance.

- This links back to the IPT - maritime security is a key issue, and one of the key reasons states are concerned with it is the issue of competition and conflict in the South China Sea. What this section is therefore doing is providing an economic reason for the UK to be concerned with maritime issues worldwide, but also states that challenge the frameworks that underpin maritime security. China’s interpretation of the scope of its territorial sea, and its rights to bar passage through it is in opposition to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which permits innocent (e.g. non threatening) passage through territorial waters.

- “the most innovative and effective for their size in the world” - This recognises that the UK is reducing the size of its diplomatic corps/military. Some people think we shouldn’t be doing this!

- “Our diplomacy will be underwritten by the credibility of our deterrent and our ability to project power.” - This is a big statement of intent. Note that this covers two tradeoffs. One is whether or not the UK should actually spend money on a nuclear deterrent (it costs a hell of a lot of money), and two, whether the UK should be spending money on power projection capabilities (aircraft carriers that can be sent to the South China Sea) rather than either reducing the military entirely, or focusing it upon European defence.

II. Overview

- Last review, the UK was in the EU, now it’s not. Note that one of the key issues post Brexit is that the UK now has the freedom to sign free-trade deals with more international partners, but it has to go looking for them. This paragraph is explaining how and why the UK is going to navigate the problem of having left its major trading partners in the EU without a clear sense of direction (except “out of the EU”). Brexit was fundamentally a domestic political problem, and the UK’s foreign policy now has to cope with the consequences.

- Somewhat inarguable statements, but note the parity of serious and organised crime with terrorism and states in terms of threat.

- This signals an investment in “cyber power”, which means money being used to build organisations, train and retain cybersecurity professionals, and develop cybersecurity capabilities across government. Note that a key inescapable problem is that the money the government will pay said professionals is much lower than the money that they could make in the private sector, and the private sector needs them.

- “Our commitment to European security is unequivocal” - during the negotiation processes for leaving the EU, the Article 50 letter sent by then PM Theresa May’s government to the EU was interpreted as putting UK/EU security cooperation in play for the purposes of negotiations. Link here.

- I say “rules-based international system”, you say “rules-based international order”. Note that in the PM’s intro, he said “That open and resilient international order is in turn the best guarantor of security for our own citizens.” but this paragraph is open to fluctuations in international order. One way of interpreting this is accepting change, however the last sentence “A defence of the status quo is no longer sufficient for the decade ahead.” indicates that the UK is turning to proactive re-shaping to counter challenges to the current international order.

- The “shared rules in frontiers element” here points to focusing UK engagement in diplomatic processes that are seeking to generate international consensus. There’s a couple of key issues relevant to war and defence here, notably the relative lack of agreement regarding international law relevant to cyber attacks and cyber security, and the re-focused interest on military activities in space. Space has always been a militarised domain, but now states such as China and Russia are demonstrating anti-satellite missile capabilities to show that they could destroy satellites required for military command and control upon which US/UK militaries depend.

- Somewhat aspirational - the UK economy has been hammered by Covid and Brexit, but at the same time it hasn’t collapsed as some doomsayers predicted. This paragraph also perhaps reflects elite consensus, in that foreign policy issues usually aren’t that big a feature in most people’s day-to-day lives and worries until a crisis kicks off.

- The elephant in the room here is that many people aren’t sceptical of the merits of globalisation, they are positively hostile to it. Note the tension between the IR that is predicated on global connections and free-trade, and the fact that political discourse in the UK since Brexit shows high levels of popular appeal regarding re-nationalising production and manufacturing, and reducing the UK’s reliance upon the EU, etc.

- Mostly covered previously, but note that the strategic framework is only extending to the funding period.

- The IR now matters to you, dear civil servant, even if you never previously thought national security was what you do.

- “CTRL-F for your topic of choice, dear citizen/EU partner”

- This is all fairly uncontroversial, until you hit “prosperity”. The UK is a very rich country by global standards, but also one with high levels of wealth disparity and economic opportunity. One feature of this is persistent disparities between economic opportunities in the north of England and the relatively affluent south east of England. The Conservative victory in the 2019 election saw Conservatives take seats in previous Labour strongholds across the north of England, on the back of a manifesto commitment of “levelling up every part of the UK” Link - p.26. At the point that the IR was published, “levelling up” had been bandied about for almost 2 years without any clear definition of what it meant in practice. The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) was re-named the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) in September 2021, but the promised government white paper (policy document) on levelling up has yet to be published. Hence the use of “levelling up” in the IR.

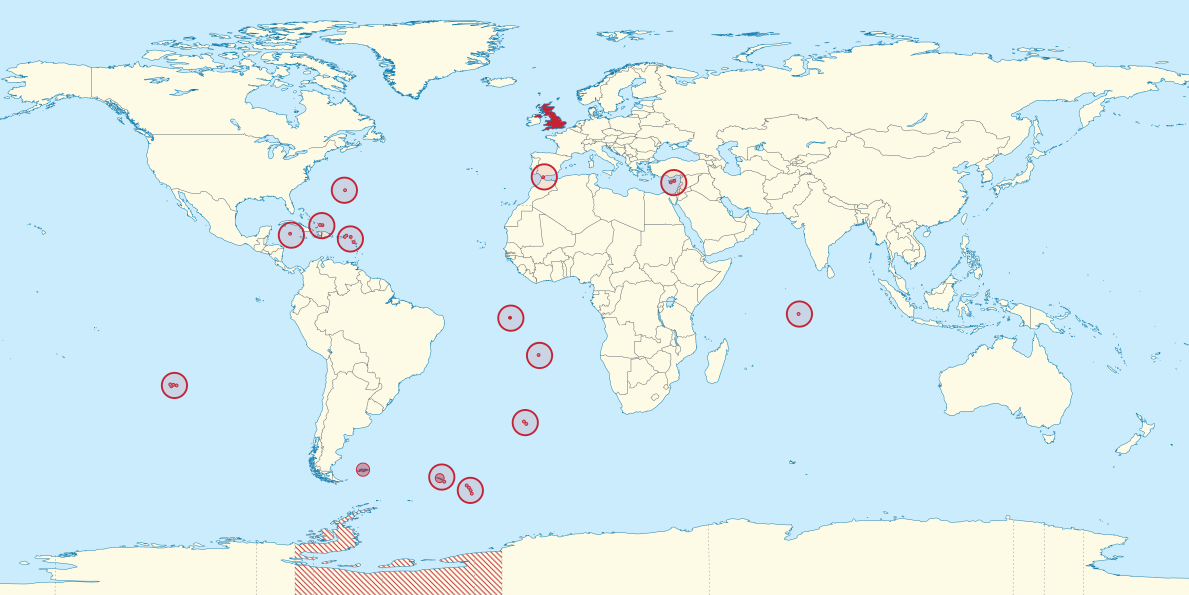

- Ah, Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. Funny things, those. The Crown Dependencies are (relatively speaking and for present purposes only) not that important, consisting of three islands with their own legislative assemblies near to the United Kingdom. On the other hand, British Overseas Territories are a bit further away:

(License: CC SA-BY 3.0, Wikipedia user Rob984) These holdovers from the British Empire means that when the UK talks about defending itself, it implicitly means defending a collection of territories that cover roughly half the globe.

(License: CC SA-BY 3.0, Wikipedia user Rob984) These holdovers from the British Empire means that when the UK talks about defending itself, it implicitly means defending a collection of territories that cover roughly half the globe. - Fun fact - these “shared values” are different to the “fundamental British values” of “democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance for those with different faiths and beliefs” which education providers have a legal duty to promote in nurseries and schools. While there has always been some notion of shared values in the UK, the 2011 update to the UK’s Prevent strategy Link for countering extremism placed an emphasis on “British values” in part because it needed to define extremists as people who rejected them. Note that the shared values identified in the IR include “a commitment to universal human rights” which is remarkable because a regrettable aspect of the UK’s political discourse is that some sections of the UK’s public and political elites espouse contempt for human rights (notably the human rights of migrants and refugees) on almost a daily basis.

- Without using the “liberal international order” (or similar) term, this is pointing towards something like a grand strategy for the UK - promote an international environment that enables democracies like the UK to flourish.

- …but we’ll need to work with some nasty people from time to time, because them’s the breaks.

- New word that appears twice in the IR, but is still important: “diaspora”. Another challenge for the UK is that there are a lot of UK citizens abroad, and if the government wants to keep them safe, then it can’t circle the wagons and shut the UK off from the world. At the same time, note the language further down “…the safety of our citizens at home…”. This section is important in that it 1) defines a core area of security (UK and Europe), and 2) says diplomacy comes first elsewhere, and 3) highlights the CPTPP. The CPTPP is a trade area centred on the Pacific that the UK is now looking to join to expand its trade in this region Link.

- Note: there are many aspects of the UK’s foreign policy that aren’t highlighted in this paragraph. If we’re to judge the UK on its actions since 2019, that also includes things like its approach to Brexit negotiations (and their fallout), and continuing to sell arms and military services to Saudi Arabia despite its ongoing war in Yemen Link.

- This paragraph should be read in conjunction with the prior references to soft power. One of the points that the UK is making here is that their diplomatic skill and position makes the UK well positioned to lead on these kinds of multilateral agreements.

- Read the good things in this paragraph in conjunction with the UK/EU “disagreement” over Covid-19 vaccine supplies earlier in 2021 over who gets access to AstraZeneca’s vaccine first Link.

- Big paragraph! This is a bit of a grab-bag of worthwhile activities. Some points:

- The Mali deployment is officially called Operation Newcombe Link, and the Lieutenant Colonel in charge of British forces there recently decided to discuss on Twitter Link that they’d killed some armed fighters after coming under fire Link which had some people troubled Link. This is also an example of the way the British Army is seeking to re-design what it does.

- Although counter-terrorism legislation is a bit out of scope for this annotated guide, the National Security and Investment Bill Link is important to note. The problem for a free-market capitalist country like the UK is that free trade and market capitalism means that states with a lot of cash in hand - say, China - can come along and buy up strategically important companies according to the rules of the market (e.g. buy all the shares). This bill enables the government to scrutinize and potentially block acquisitions in areas of the economy that the government thinks might give rise to national security risks.

- Two things:

- The Magnitsky sanctions are a great step forwards (see Link for how they work). Bear in mind that a persistent issue in UK politics is the fact that a lot of money associated with corrupt regimes is laundered through the UK economy. In short, there’s a tradeoff between eliminating money laundering/tax evasion and the success of a cornerstone of the UK’s economy because moving from a “light touch” regulatory approach is likely to result in business being diverted elsewhere Link.

- The mention of China breaching a legally-binding agreement refers to the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, which guaranteed Hong Kong’s governance after it was handed back to China in 1997. China’s imposition of repressive legislation breaches the agreement, but then China doesn’t think the agreement is binding anymore. It is worthwhile considering that the only lever the UK appeared to have in this situation was to offer a section of Hong Kong’s population the right to live and work in the UK.

- Couple of points:

- Why is an efficient, smart and responsive border going to enhance the long-term prosperity of the UK? Good question. The 2025 UK Border Strategy Link is primarily about implementing efficient border controls now that we need them for trade with the EU. It is also about keeping out “irregular migration” e.g. refugees and economic migrants that go around official pathways to the UK. The fact that these pathways have been reduced or dismantled is besides the point, here.

- ARIA is the UK’s attempt at a DARPA (the USA’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Link) but without the explicit military focus. In the old days - when DARPA was simply the Advanced Research Projects Agency - ARPA funded a lot of basic research connected to the strategic or security concerns. You’re probably reading this on the internet, and ARPA invetned/created ARPAnet Link, which was a fore-runner of that. In 1973 the US changed the way DARPA was funded, restricting it to funding projects with direct military applications, but ARIA appears to be an agency attempting to recreate the ARPA heyday, in the UK.

- Build back better - see note to paragraph 2 from the PM’s foreword.

- Ask yourself when you have ever seen someone say they need a short term strategic approach, or whether a government needs a dis-unified approach to tackling problems.

- No additional comments

- No additional comments

- “We must be prepared to compete with others” - “others” is too open for this to really be meaningful

- “Maintaining a long-term perspective will help us navigate the path ahead” - the IR implicitly defines long-term at 10 years total, 5 years funded.

- Keep in mind that the IR is aimed at the UK’s civil service, this is why it’s talking about “bring all the instruments available to the Government together” (in civil service-ese: “That means all of you.”) and why it isn’t being explicit (in civil service-ese: “There’s no way we could hope to battle out every issue before publishing this.”).

- See previous discussion of SR 2020. Note the Treasury is probably happy at the line “Future SRs will also be informed by this Framework and will provide further opportunities to align resources with ambition.” since that gives various departments the opportunity to make a case for funding to the Treasury, and the Treasury the opportunity to say “No”.

- Ooh, footnote! The 2019 Queen’s Speech (in the UK, this outlines the laws that the Government intends to bring forward at the start of the parliamentary session) included an aim to bring forward legislation on espionage, to “Provide the security services and law enforcement agencies with the tools they need to disrupt Hostile State Activity.” Link, p.84. This reflected the way in which Theresa May’s government sought to coordinate responses to the Salisbury attack Link. By the time this legislation was brought forward, Boris Johnson’s government had switched to state threats, so the bill became “Legislation to Counter State Threats (Hostile State Activity)” Link. Note that this is also the first time Russia gets named in the IR, but that’s probably a coincidence.

- Collective action with allies is a standard feature of international politics, but the distinction here between allies and partners matters, as it is indicating the UK might act alongside states that it doesn’t share core collective security arrangements or longstanding commitments to. Equally, co-creation is important in the sense that it exists here as something distinguished from collective action (which is a term usually reserved for international politics/diplomacy). Taken with the points later in the paragraph, it nods towards the UK working in joint projects particularly in the science and technology sector.

- History time: The National Security Capability Review Link followed from the 2015 SDSR, functioning as both an annual report on the progress of the SDSR, and implementing the “Fusion Doctrine” as a means of conducting national security policy. This “Chilcot-compliant approach” (NCSR, p.10) is termed as such because it is in part a response to criticisms about the UK’s strategic decisionmaking processes raised in the Chilcot Report, the report of the Iraq Inquiry into the UK’s involvement in the 2003 Iraq War (so named because the inquiry’s chair was Sir John Chilcot). You can read the Chilcot report online, and it is a great resource, but the whole thing runs to 2.6 million words link. The Fusion Doctrine created lead roles for key national security priorities within the UK’s civil service, as a means of ensuring that the whole range of the civil service (and thereby the UK’s government) could contribute to these goals in an effective manner.

- Some people might not like the fact that the whole of the UK’s civil service is getting into the national security business, this paragraph is an attempt to explain why it is thought necessary.

- Three points:

- The FCDO was the product of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and the Department for International Development. Note that many development experts were against this, as they felt that bringing the delivery of development aid explicitly back into the realm of the FCO would result in it being used for political reasons rather than to best effect.

- The Integrated Operating Concept 2025 is a statement of the current British approach to the utility of force. The IOC 2025 was substantially updated in August 2021 to reflect alignment with the IR itself link.

- This is pointing to things that don’t fit well within a single contemporary UK department of state. The situation centre is an attempt to copy the American model of having a crisis room in the White Room with information fed into decisionmakers. This reportedly costed £9 million link. Likewise the CTOC reflects the fact that the UK’s tools for responding to terrorism are distributed across a number of different organisations. Previous integration, such as the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre (JTAC) brought together these departments in one location link, whereas CTOC is aimed at increasing the integration of direct responses to terrorist events. The National Cyber Force reflects the fact that both Defence and Intelligence require a pool of technical capabilities related to cyber security and cyber attacks that are most efficiently served by a single organisation link. The “national capability in digital twinning” is rather obscure, but is about creating capabilities for modelling large real-world systems on computers that are updated in real time using real data. So, for example, if you have a bit of critical national infrastructure, you might be able to get a better understanding of what is going on (or wrong) with it, and be able to create a range of predictions about future behaviour, faster than you might otherwise be able to do.

- The UK is going to do everything at the same time in an integrated fashion.

- The importance of this is that it serves as a one-stop-shop for previous policy goals.

- i) Again, the US is identified as the UK’s key partner (so if you want to know how the IR is going, diplomatic spats with the US is a good metric to watch). The “Five Eyes” is a very close intelligence sharing relationship between the UK, US, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Although not directly comparable in terms of organisations/budgeting arrangements, the UK spends between 2.5-3 billion pounds on intelligence per year, the US spends something in the region of 80 billion dollars, so it is definitely a relationship worth keeping from the UK’s perspective!

- ii) NATO again. The “remain the leading European Ally” bit is again how the UK sees itself (and points to the fact that NATO is a transatlantic alliance with the US), but countries like France might disagree. CTRL-F for the prior discussion of the 2% target. Article 5 is the key collective security guarantee in the NATO treaty, which requires NATO allies to consider armed attacks against one ally to be an armed attack against all of them. So what this is saying is that the UK is committed to potentially using the full spectrum of what it has, including nuclear weapons, should someone commit an armed attack against a NATO state.

- iii) The National Crime Agency is the UK’s national-level agency for criminal investigations (formerly the Serious Organised Crime Agency). For people outside the UK, it might be slightly hard to believe that the UK got by without either for most of its existence, with the Metropolitan Police taking the lead on some national crime responses.

- iv) CTRL-F for prior Magnitsky reference.

- v) UN SDGs are a global set of goals where rich states seek to aid less developed countries to collectively achieve some big targets such as zero poverty/zero hunger/gender equality/etc. There’s 17 in total: link.

- vi) Following from the above, this is one specific aspect of the SDGs that the UK is leaning into. Policy available here: link.

- vii) When reading this section, keep in mind prior comments about Brexit (hence the “independent trade policy” bit). The Investment Security Unit, located in the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), administers the National Security and Investment Act, which is the UK’s way of ensuring that while championing free and fair trade, other states (or state-backed enterprises) can’t buy up the UK businesses and assets in a way that might pose a threat to the UK. link.

- Okay, again, large number of points:

- i) “regulatory diplomacy” refers to diplomatic activities that design and maintain the political and economic rules of the planet. It ranges from the very high-level abstract principles stuff, down to technical regulatory frameworks that enable pretty much anything trade/production related to function. The “norm and standards governing technology and the digital economy” bit is important because computers and computer networks, and services built upon them, are creating lots of awkward issues in international politics. One reason for this is that the scale of centralised service provision (e.g. a single company, like Facebook or Salesforce) means that the rules governing one domain (say, the US or the EU) effectively become the rules for a wider section of the planet (unless that wider section doesn’t care about market access). Convening power refers to the fact that many multilateral processes rotate leadership roles between members, giving states the chance to push forwards the process with their own focus for a bit. Lastly, one of the hidden ways that international politics works is by attempting to stuff any given international organisation with people from your own country, subject to the rules and processes of that organisation, hence the “win elections” bit.

- ii) Again, don’t say “Brexit”.

- iii) ICF = “international climate finance”, the UK’s committed spending to support developing countries respond to climate change link.

- iv) “own-collaborate-access framework” - this is because the UK understands that to get what it wants (a strategic edge in science and technology), it will need access to some technologies that it won’t be able to support domestically. You have probably heard of AI and quantum technologies. Engineering biology is about the design and building of biological systems, sort of like synthetic biology (redesigning existing organisms or giving them new abilities). These kinds of technologies are crucial to stuff like food production and medicine.

- v) We are going to develop the capability to break into your computer systems, but we are going to be responsible about it.

- vi) Space Command is a new bit of the UK armed forces link. Why does the UK need its own space programme? Well, the UK has a strong background in satellites, but previously was part of the EU satellite programmes. Now it is a third-party country, so having to negotiate working access link.

- vii) As noted above, the Indo-Pacific is a big deal that we’ll f go into in depth.

- viii) We recognise that China is a big deal, a threat, and something we need a better understanding of. Also if we don’t trade with China, or get China to cooperate on climate change, we’re screwed.

- ix) Five point plan first aired at the UN General Assembly in 2020 link. Note that the UK is the second largest current funder of the World Health Organisation link.

- x) More on this later, but the basic point here is that the UK is going to do more “persistent engagement” on top of preparing for war. The Future Combat Air System is the UK’s Tempest, which will replace its fighter jets (Typhoon/Eurofighter). This was originally a UK/France cooperation, but France then opted to work with Germany and Spain on their own next generation fighter, the innovatively-titled Future Combat Air System (FCAS).

- xi) See state threats note above.

- xii) See prior notes on the situation centre and digital twinning.

III. The national security and international environment to 2030

- No comment

- Points:

- Geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts: Remember, this is about a global economic shift towards Asia in general, not just China.

- Systemic competition: More conflict, more of the time, with less things off limits. One point to mention about geopolitical/economic blocs is that the UK has just left one, so the more these blocs cohere and matter as mutually exclusive entities, the worse it is for the UK.

- Rapid technological change: See above notes.

- Transnational challanges: What’s interesting here is that the UK has plumped for climate change and biodiversity loss as key challenges ahead of things like terroristm.

- Fair to say the UK is not preparing for the realistic optimum scenario.

- Geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts.

- China: China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a massive set of infrastructure projects that China has invested in across the planet. It is explicitly political in that it is designed to build partnerships and extend Chinese influence abroad. One aspect of the initiative that is becoming more apparent is the predatory nature of some of these deals (e.g. signing states up for finance agreements that they are unlikely to be able to repay). That aside, we must remember that helping states out with finance and engineering expertise (etc) is something that pretty much all big states do.

- Shifts in global balance: Again, the growth is going to be in the Indo-Pacific, and, as a service economy, this is where the UK’s future trade growth lies.

- Global growth: Growth is a big issue because the world economic system depends upon it. The moment a country stops growing, bad things start to happen, people lose their jobs, high paying jobs aren’t created, etc.

- Challenges: The UK economy reaps the benefits of open global trade and capital flows. Since the UK is no longer in a big trading block, it is also vulnerable to protectionist policies and being picked on by bigger economies.

- Decreasing global poverty: Remember poverty reduction is a UN SDG.

- Improvements in education: Good news!

- Changing demographics: The UK is an aging country, with slow population growth. The median age is something like 40, and about 20% of the country is over 65 (around retirement age). Compare that to Niger, where about 50% of the country is under the age of 15. One of the unstated things here is that the needs of a slow-growth population full of retirees is not likely to be the same as one full of teenagers. So, will the UK’s needs align with all those fast population growth countries in future?

- Geopolitical importance of middle powers: The UK writes about a place for itself in the world without mentioning itself.

- Challenges to democratic governance: If you tot up slow global economic growth, demographic growth, and the rise of big transnational corporations hoovering up cash to a select number of states, you get angry people upset by the current world order. What this section is pointing to is that the ways in states are going to tamp down on such dissent will vary.

- Systemic competition.

- Competition between political systems: As a background to this, during the post-cold war period there was a wave of democratisation across the world. Then there has been a period of prolonged “democratic backsliding”. As noted previously, the world order that won the cold war favoured liberal democracies, and now autocracies are pushing back against that system.

- Competition to shape the international order: The “non-state actors” in the science and technology space here are big corporations, not ISIS.

- Competition across multiple spheres: This is focused upon “hybrid warfare” or “grey-zone competition”, which for some is brand spanking new, and for others simply old statecraft refracted through the lens of the 21st century. One thing to keep in mind here is that the UK’s toolkit for deterrence doesn’t appear to be deterring informational attacks (“disinformation” etc) or cyber attacks linked to state actors (ransomware etc).

- Deteriorating security environment: CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear) proliferation is a standard problem in international relations. The proliferation of advanced conventional weapons and novel military technologies is, however, a pressing issue at the moment. For example, the use of small drones by non-state actors requires the UK to adopt a range of counter-drone systems to protect its military. Secondly, the proliferation of precision strike capabilities means that countries like Iran can reliably hit specific targets at range, which they used not to be able to do. The key issue is technology transfers between states and proxy non-state actor forces that could make them extremely dangerous to conventional forces (like the UK’s). Conversely, consider that the UK aiding Kurdish forces with RAF strikes to fight ISIS is pretty much the same problem, but from our perspective.

- Growing conflict and instability: The world now has a large number of internationalised civil wars, and the problem is here to stay.

- Economic statecraft: Key point here is control of rare earth minerals, as these materials are essential to the creation of many technologically advanced products and systems. China has a relative stranglehold on the production of rare earth minerals (in that through a combination of efficiency gains and state support they have out-competed other countries/companies on the open market), and therefore can leverage control over these materials as export goods.

- Cyberspace: Remember that commercial cyber attacks are a big deal (see “Ransomware”), and that some states have leveraged criminal groups that are built around cyber attacks to support their own state capabilities to conduct cyber attacks. On the point about digital freedom/authoritarianism, again the conflict over regulation/values of big companies is a key issue, especially since they all want to access the Chinese domestic market.

- Space: Space has always been a military domain, but it is getting increasingly hard to manage.

- Rapid technological change.

- A rapidly changing landscape: Bear in mind that when people talk about the acceleration of technological change that the greatest period of technological advance in history was probably the period from the 1870-1970, which began without modern internal combustion engines or gas turbines, and ended with human beings on the moon. These days technology always changes and there aren’t really good ways to compare rates of change across technological domains/use cases.

- S&T as an arena of systemic competition: Again, read this as a laundry list of things that the UK is up against, not being a tech “superpower” itself.

- New challenges: Read this as a laundry list of probably non-resolveable problems confronting open societies these days.

- Technology and data standards: The UK would like a role in developing governance standards for these frontier spaces since its economic plan depends upon them, at the same time, will it have a seat at the table if the US/EU/China arbitrarily agree on something?

- Transnational challenges.

- Climate change: Basically, we’re all screwed, but some are more screwed than others. The essential tension is that “decarbonisation” causes short/medium term economic hits, whereas non-decarbonisation is going to kill a lot of people, and perhaps the planet. Politicians are more amenable to political pressures caused by short-term issues than long-term ones.

- Biodiversity loss: Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962. Check it out.

- Global Health: When you have a global economy that has 8 billion people and a substantial fraction of them travelling in aeroplanes, you get infectious disease outbreaks. Antimicrobial resistance is, however, a key long-term issue - more and more microbes are becoming resistant to antibiotics, on the long term, this threatens to take us back to the pre-penicillin era, where routine surgery can kill you. Fingers crossed that if you’re reading this you’ll still be able to get a hip replacement in 60 years if you need one.

- Migratory flows: Europe is the destination for a lot of mass migration, which is why Europe has thrown up border walls and detention camps beyond its borders. The UK is doing its bit by virtually ending legitimate asylum routes to the country, and training its Border Force to turn migrant boats around using jet skis link. Square all the above with the appeals to openness, democracy, liberty, values, etc, if you can.

- Radicalisation and terrorism: If you are not familiar with the UK, you should probably read up on “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland. The “resolution” of the Northern Ireland conflict in 1997 didn’t stop sectarianism, and it is an ongoing issue. With regards to the CBRN attack line, this conflates a terrorist group detonating a nuclear weapon (very unlikely but could kill tens of thousands of people) with a terrorist group making a weapon out of a chlorine canister (very easy but could also kill a handful of people), so it doesn’t actually say that much.

- Serious and organised crime and illicit finance: Note that the last line on money laundering is a serious issue for the UK, since part of the City of London’s competitive advantage lies in the “light touch” regulation that makes it relatively easy to launder tens of billions of pounds every year.

IV. Strategic Framework

1. Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology

- The bet: invest to keep the UK in the ring for science and technology governance, because that’s a good path to future influence. In history, an alternate economic strategy is to copy the innovations of others and improve on them. The current global intellectual property frameworks are designed to make this strategy non-viable. That said, succesful copying reduces the relative returns on technological innovation, so this bet/strategy therefore depends upon strong intellectual property regulations to prevent up-and-coming states copying their way to near parity.

- Countries typically claim scientific discoveries, when they often occur in the context of international scientific interest/discovery. Graphene is the thinnest material currently known, consisting of a sheet of 1 atom thick carbon molecules. The UK’s claim to discovering it rests mostly on the Nobel Prize awarded to two scientists at the University of Manchester, who managed to isolate graphene in 2004 using sellotape, rather than alternate methods previously attempted in the United States and elsewhere. The reference to development of Covid-19 treatments and vaccines are likely to be better indicators of the UK’s current potential for science and technology research than the reference to discovering the structure of DNA, given that the latter occurred in 1952-1953. What this paragraph points to is ultimately the logic for state intervention to support research and development. Keep in mind that state support for science and technology might not be preferable if you are, say, a factory worker in an industry that is under pressure from overseas competition and would therefore prefer state support for production etc etc.

- Key thing to keep in mind here is the line about regulators and standards bodies. Permissive regulatory regimes might enable more innovation and faster development of discoveries. At the same time, that leaves more scope for accidentally or intentionally harmful things causing harm to the general public. This paragraph is also balancing the quite unitary “whole-of-UK effort” with the notion that the government’s role is to enable a science and technology ecosystem. In other words, it will leave the precise choices of which technologies to fund to the market.

- Cyber power is discussed at length shortly afterwards. The key thing here that might be contentious is the reference to “offensive cyber” - this is the organisations and personnel required to conduct operations that break into the computer networks controlled by companies and states abroad.

- Venture capital investment is a signal that the global financial markets think the UK is a good place to bet on making money. Without wanting to go too deep into finance 101, venture capital usually refers to backing companies at an early stage, enabling them to scale up operations/launch products necessary to launch at a decent initial public offering of shares. If a company has a great product but doesn’t have the money to launch it on the market, then the great product might as well not exist, hence the need for investment. This is also sometimes called “casino capitalism” because venture capital funds (big blocks of money that investors pull together to invest in a defined set of industries) operate on the premise that a lot of their bets will fail prior to IPO, but some will make so much money that there will be a good overall return for the fund.

- Following from the above, another problme facing innovators/start-ups is that if you don’t have a route to market (lacking investment), the way to get some return on your efforts is to sell the rights to someone else. The problem hinted at here is that the UK might be a hotbed for innovation, but if all the ideas are bought up by foreign companies who then reap the rewards, that doesn’t do much for the UK’s economy.

- So, the UK needs to create a world for innovators, but it needs to prevent all those innovations getting snapped up by other people. It needs to help companies move from prototype to product fast, but to do so in a legal and ethical manner. This section is a dance between free-market ideas, and state intervention. From a “pro-growth, pro-innvation” regulatory perspective, law and ethics might seem to be onerous state constraints.

- The UK R&D Roadmap was announced in 2020 link. The 2.4% target is a substantial improvement (current R&D spending is about 1.74%, so it’s roughly a 33% increase in relative spending) link. The headline investment here is the £800 million ARIA funding (discussed previously).

- The Global Talent Visa scheme is currently a flop, with no applications as of late 2021 link.

- More discussion above and below, but remember that preventing people from buying/selling IP runs counter to attracting talent and investment to the UK

- Basically, the government is going to make the call on how it will support research/development on a case by case basis. If you’re into quantum, the government will throw money at you, if you’re in something the government defines as “access”, you might get some support for investment. Note that this is also linked to the strategic supply of a technology, envisioning a future where some might otherwise be only owned/produced by potentially hostile states.

- Silicon Valley is where a lot of the US’s leading technology companies are. The Technology Envoy is a diplomatic post within the FCDO link. Horizon Europe is the EU’s collective scientific research budget, with a total budget of 95.5 billion Euro link through to 2027. There was significant uncertainty about the ability of UK researchers to continue engaging with this after Brexit, but the Government is now supporting association with Horizon Europe, much to the relief of academics up and down the UK. See above for the notes about the UK’s participation in EU satellite programmes like Copernicus.

- Nothing to add

- 85% = defence industry is reliant upon government money for innovation.

- The MoD science and technology strategy is here: link. £6.6 billion in funding is a large chunk of money, but over 4 years means that it is a little less impressive in R&D terms (relative to, and considering, the amounts of venture capital that are washing around the world at this point). Space is a relatively capital-heavy area of investment and research. Directed energy weapons are lasers to you and I, and advanced high-speed missiles refers to hypersonic weapons, a class of weapon that can deliver strategic paylods (e.g. nuclear weapons) while evading traditional ballistic missile defence systems. Note the language here leaves open whether the UK is investing in such systems, or countermeasures. The Defence and Security Industrial Strategy link is a key document for an industry reliant upon government spending to guide its investment decisions.

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

2. Shaping the open international order of the future

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

The UK in the world: a European country with global interests

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

The Indo-Pacific tilt: a framework

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

3. Strengthening security and defence at home and overseas

NB: Insert on the Nuclear Deterrent is split out to the end of the section

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

The nuclear deterrent

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

4. Building resilience at home and overseas

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

V. Implementing the Integrated Review

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed

- To be completed